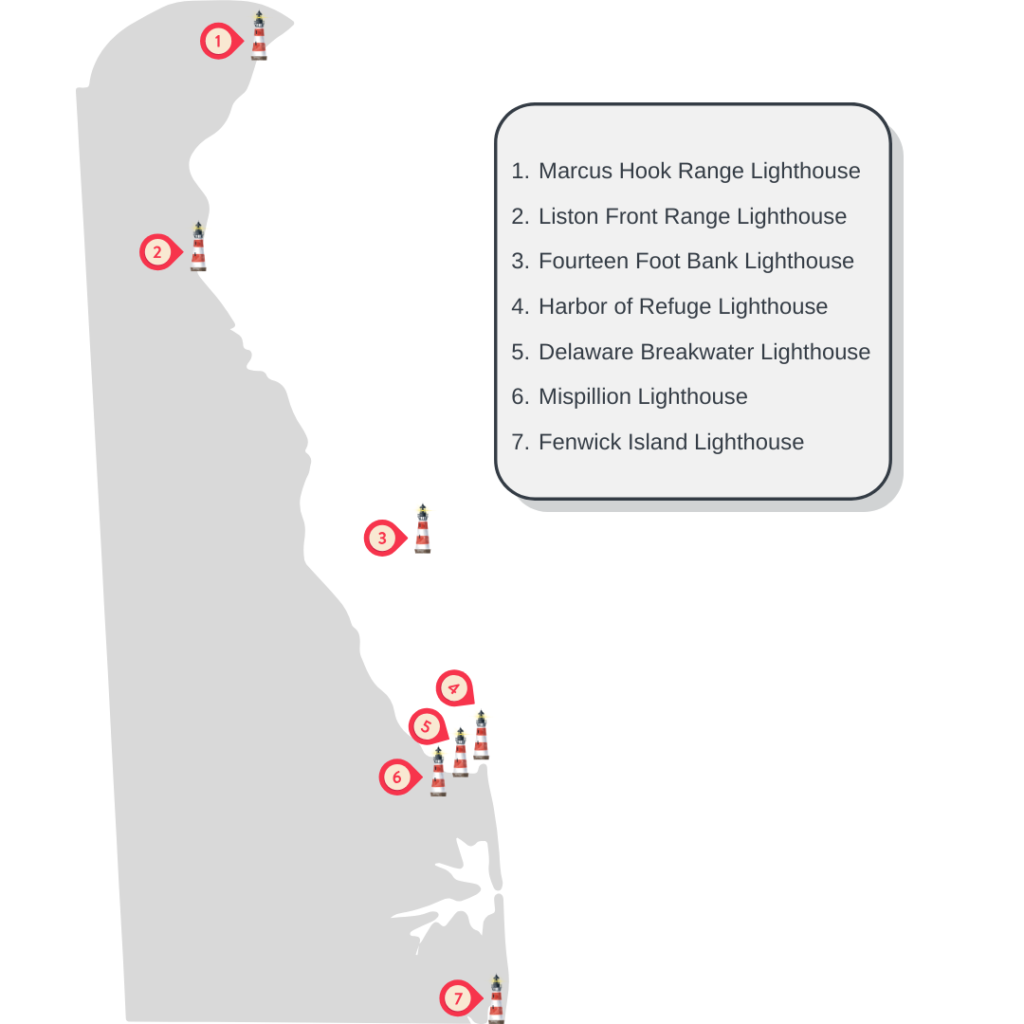

Delaware’s Historic Lighthouses: Beacons of Maritime Heritage

For centuries, lighthouses have served as crucial navigational aids along Delaware’s coastline, guiding ships safely through treacherous waters and marking important maritime routes. These historic structures stand as testament to Delaware’s rich maritime heritage, each with its own unique story to tell. From the northern reaches of the Delaware River to the southern Atlantic coast, these beacons have witnessed countless vessels pass through their waters, playing vital roles in the region’s commerce and maritime safety.

1. Marcus Hook Range Lighthouse

The Marcus Hook Range Lighthouse system, established in Delaware, represents an innovative response to early 20th-century maritime challenges. The system was born from necessity in 1916 when Congress approved $80,000 for its construction, following the dredging of a new thirty-five-foot channel near Schooner Ledge in the Delaware River. This range light system would become the last manned range lights constructed along the Delaware River.

The original system consisted of two complementary structures: a front range light and a rear range light. The front range light, built in 1918, stood about 100 yards offshore in the Delaware River atop a twenty-foot-square concrete crib. This seventy-two-foot structural steel tower initially operated on acetylene gas stored in tanks that could power the light for three to four months at a time.

The rear range light, completed in 1919, showcases elegant Colonial Revival architecture with its reinforced concrete tower and attached keeper’s dwelling. The tower features buttressed corners and rises to an impressive height, offering its keeper a panoramic view of the Delaware River from its four-foot-wide balcony. The light originally housed a fourth-order range lens that produced a fixed white light of 24,000 candlepower, visible from 278 feet above the river.

In a significant modernization in June 2019, the system was reconfigured. The original front range light location became the new rear range light, and a new front range light was established 1,866 yards upstream. Today, the range lights continue their vital role in maritime safety, displaying red lights at night and white lights during daylight hours.

2. Liston Front Range Lighthouse

Established in 1904, this lighthouse emerged from necessity when improvements to the Delaware River shipping channel rendered the older Port Penn Range Lights obsolete. The tower we see today was completed in 1908, replacing a temporary structure that had served as the initial beacon.

What makes this lighthouse particularly special is its architectural heritage – it’s the last remaining wood-frame lighthouse in Delaware. The structure showcases the meticulous standards of lighthouse construction during that era. The two-story dwelling features a distinctive hipped roof crowned by a watchroom and lantern room.

The light’s original fourth-order range lens, manufactured by the Macbeth Company of Pittsburgh, remains in the lantern room today, though no longer active. This lens once produced an occulting light pattern that was visible for two seconds and eclipsed for one second, guiding countless vessels through the Delaware River channel.

Today, while the structure stands within the private riverside community of Bayview Beach, its historical significance has been formally recognized with its placement on the National Register of Historic Places in 2004. Recently, in 2023, the lighthouse changed hands again when it sold for $950,000, continuing its journey as a preserved piece of Delaware’s maritime heritage.

3. Fourteen Foot Bank Lighthouse

Standing sentinel in Delaware Bay, Fourteen Foot Bank Lighthouse marks a critical oval shoal situated three-and-a-half miles from Delaware’s shore and just over ten miles northeast of Mispillion Creek. Its name derives from the fourteen-foot depth of water found at this challenging navigation point, which previously claimed many vessels before it’s construction.

The construction in 1885-1887 represented a remarkable feat of engineering for its time. Engineers employed the innovative pneumatic-caisson method to secure the foundation, a technique that had only been used once before in American lighthouse construction. The process involved sinking a massive iron cylinder into the shoal using compressed air chambers. Teams of workers, earning just $2 per day, labored in pressurized underwater compartments lit by paraffin candles, methodically excavating sand from beneath the caisson as it gradually sank thirty-three feet into the shoal bed.

The building itself showcases Classical Revival architecture, featuring a two-story cast-iron dwelling crowned by a square tower and octagonal lantern room. The structure includes three distinctive gables and, rather ingeniously, even incorporated a cantilevered privy extending over the edge of the foundation cylinder. The entire project came in under budget at $125,000, quite remarkable for such an ambitious engineering undertaking.

The first light shone on April 10, 1887, featuring an innovative characteristic: white light with red sectors specifically positioned to warn ships away from the treacherous Brown and Joe Flogger Shoals. In 1918, the light was upgraded with a revolving fourth-order Henry LePaute lens, producing a white flash every ten seconds.

Today, while still serving as an active aid to navigation, the lighthouse has evolved beyond its original purpose. It has housed sophisticated monitoring equipment for the University of Delaware’s Delaware Bay Observing System, collecting vital weather and oceanographic data. In 2007, it entered private ownership when Michael L. Gabriel purchased it for $200,000, with plans to create a unique summer residence that would include a small brewery utilizing desalinated bay water.

The light’s original fourth-order Fresnel lens, a masterpiece of 19th-century optical technology, is now preserved and displayed at the Lewes Historical Society’s Maritime Museum, allowing visitors to appreciate this important piece of maritime heritage up close.

4. Harbor of Refuge Lighthouse

The story of this lighthouse begins in 1890, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers determined that the existing Delaware Breakwater’s sixteen-foot depth was insufficient for the era’s larger vessels. This led to an ambitious project: constructing a new 7,950-foot breakwater to create a deeper harbor of refuge.

The lighthouse’s history encompasses two distinct structures on the same site. The first lighthouse, completed in 1908, emerged from necessity after a devastating 1903 storm destroyed the temporary beacon and claimed the lives of five sailors aboard the schooner Hattie A. Marsh. Despite knowledge that the location faced “extremely dangerous” conditions, budget constraints led to the construction of a wooden hexagonal structure atop a concrete foundation – a decision that would prove challenging.

The wooden structure endured tremendous beatings from the elements. Keeper Robert C. Taylor’s logbooks tell dramatic tales of two powerful storms that each shifted the entire building two inches on its foundation. The February 1920 storm proved particularly devastating, sweeping away all outbuildings, tools, and even the keeper’s rowboat.

By 1926, after years of abuse from the elements, the wooden structure was replaced by the cast-iron tower we see today. This more robust lighthouse was built not only to better withstand the harsh environment but also to take on the role of the failing Cape Henlopen Lighthouse. The new structure featured three stories of living quarters within its conical tower, supported by a cylindrical pier specifically designed with a flaring upper section to deflect powerful waves. The light was equipped with a sophisticated fourth-order lens producing a 22,000-candlepower flash every ten seconds and a compressed-air fog signal that blasted three times every 45 seconds.

Today, the Harbor of Refuge Lighthouse continues its vital role under the care of the Delaware River and Bay Lighthouse Foundation, which acquired ownership in 2004. The foundation has orchestrated several major preservation efforts, including a quarter-million-dollar rehabilitation in 1998-1999 and the installation of a custom-designed dock in 2016 that allows public tours. Most recently, in 2017, the building received a complete exterior painting and interior restoration, enabling it to welcome visitors once again and share its remarkable story of maritime preservation and perseverance.

5. Delaware Breakwater Lighthouse

The Delaware Breakwater Lighthouse, located at the entrance to Delaware Bay near Cape Henlopen, Delaware, stands as a testament to early 19th-century engineering and maritime safety. This lighthouse was built to protect vessels navigating one of the most perilous stretches of the Atlantic coast.

In response to mariners’ pleas for a safe refuge, the U.S. government initiated construction of a breakwater at Cape Henlopen in 1828. By 1869, this stone structure, built from over 835,000 tons of quarried stone, stretched 2,586 feet in length. The breakwater provided a crucial harbor of refuge for ships, accommodating as many as 200 vessels during severe storms.

The first lighthouse on the breakwater, established in 1849, was a stone keeper’s dwelling with a fixed red light. Over the years, enhancements were made, including the addition of a fog bell in 1855 and an upgraded Fresnel lens. As maritime traffic grew, the Delaware Breakwater East End Lighthouse was constructed in 1885 to replace an endangered beacon at Cape Henlopen. This new structure was a four-story iron tower topped with an octagonal lantern, standing 51 feet high.

By 1913, the light was equipped with a reinforced oil house and continued serving mariners until automation in 1950. In 1996, the Coast Guard decommissioned the light, and it was transferred to the State of Delaware. Restoration efforts led to public tours in 2004, offering visitors a glimpse into the challenging life of lighthouse keepers.

Today, the Delaware Breakwater Lighthouse is managed through a partnership between the Delaware River & Bay Authority and the Delaware River & Bay Lighthouse Foundation. After a period of inactivity, tours resumed in 2017, allowing modern-day explorers to experience the unique maritime history and stunning coastal views this iconic beacon offers.

6. Mispillion Lighthouse

The Mispillion Lighthouse, originally built in 1831 at the mouth of the Mispillion River in Delaware, was part of a trio of lighthouses constructed that year to aid navigation into Delaware Bay. This beacon was critical for guiding vessels to the inland port of Milford, a bustling shipbuilding hub where more than 400 ships were launched. Winslow Lewis, a well-known lighthouse builder, completed the first structure atop land purchased from Governor Charles Polk.

By 1839, the poorly built original lighthouse was replaced with a sturdier structure. Over the years, various improvements were made, including the installation of a fifth-order Fresnel lens in 1855. Despite its importance to local trade, the lighthouse was briefly deactivated in 1859 due to declining navigability at the river’s mouth. It was reestablished in 1873 after changes in the river’s conditions.

The second iteration of the Mispillion Lighthouse was a two-story, L-shaped dwelling with a square tower that displayed a light at 48 feet above the bay. Over time, erosion and storm damage required the construction of seawalls and riprap to protect the lighthouse. The station remained operational until automation in 1911 and was eventually deactivated in 1929, replaced by a steel skeleton tower.

After decades of private ownership and minimal upkeep, the lighthouse suffered significant damage from a fire caused by a lightning strike in 2002. Shortly afterward, parts of the structure were salvaged and incorporated into a reconstructed lighthouse in Shipcarpenter Square, Lewes. Although no longer standing at its original site, the replica preserves the legacy of Delaware’s last wood-framed lighthouse.

The steel tower that succeeded Mispillion Lighthouse was removed in 2016, marking the end of an era at the river’s entrance. Today, the story of the Mispillion Lighthouse lives on, reflecting Delaware’s rich maritime heritage.

7. Fenwick Island Lighthouse

The Fenwick Island Lighthouse, located near the Delaware-Maryland border, stands as a prominent historical beacon on the Atlantic coast. Its location was first marked in 1751 by a stone monument placed at the eastern end of the Transpeninsular Line, which settled a boundary dispute between the Calvert family of Maryland and the Penn family of Pennsylvania. The stone, engraved with the coats of arms of both families, remains just a few feet from the lighthouse today.

The need for a lighthouse at Fenwick Island became evident in the mid-19th century due to the dangerous shoals along the coast and the lack of a beacon between Cape Henlopen and Assateague Island. Congress approved funding in 1856, and construction began in 1858 under the direction of Captain William F. Raynolds. Completed later that year, the brick tower stands 75 feet high, with a third-order Fresnel lens installed to guide ships safely along the Delaware coast.

Initially, a single dwelling accommodated both the head keeper and assistant keeper. However, as families grew, an additional dwelling was added in 1881. The lighthouse operated faithfully, guiding mariners and serving as a landmark for nearly a century. In 1939, after the Coast Guard took control of the lighthouse, parts of the property were sold, and in 1978, the lighthouse was decommissioned, with its Fresnel lens removed.

Local efforts, led by Paul and Dorothy Pepper, successfully restored the lighthouse, and in 1981, it was relit with its original lens. Extensive restoration work funded by the State of Delaware in 1997 ensured its preservation, and a rededication ceremony was held in 1998, honoring the dedication of the Peppers and the community.

Today, the Fenwick Island Lighthouse, managed by the Friends of the Fenwick Island Lighthouse, continues to stand as a cherished symbol of maritime history. Restoration efforts remain ongoing, including the preservation of the nearby keeper’s dwelling, which adds to the site’s historical significance and draws visitors year-round.